AMD Sets Its Eyes On GPU Virtualization Markets, Launches FirePro S9000 and S7000 Families

A few weeks ago, in early August, AMD launched a new line of FirePro cards aimed at the high end of the workstation market. Today, it's introducing a new product family focused on server virtualization and thin client functionality. The idea here is that the entire desktop environment is stored in a central server and accessed via thin-client. There's nothing new about that basic model, but both AMD and Nvidia have put an increasing amount of emphasis on the idea of dropping a physical GPU or GPUs into the server as well.

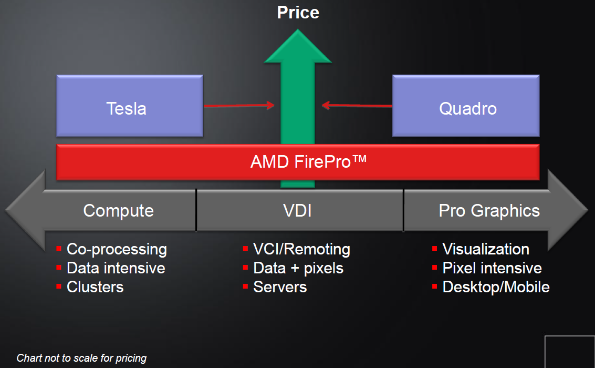

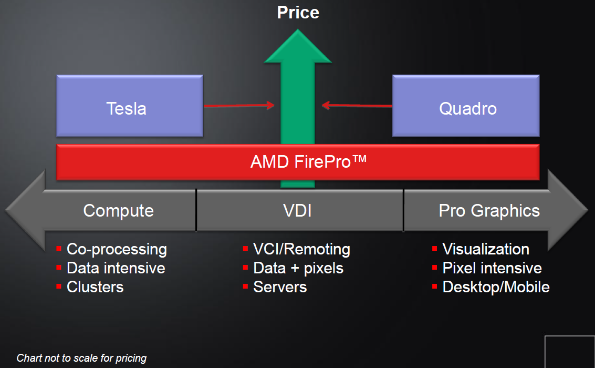

Microsoft's Remote FX, introduced in Windows Server 2008 and refined for the upcoming Server 2012, allows multiple remote clients full access to a central GPU's capabilities. VMWare and Citrix also offer support for this type of operating mode, but more on that in a moment. The big-picture idea here is that companies can save money and deployment costs by using an array of thin clients. These new cards, dubbed the S7000 and S9000, are meant to facilitate that process. GPU virtualization is a subset of the larger VDI market -- the products AMD and Nvidia have introduced are both aimed at enabling workstation-class users to access the same performance they'd see from high-powered boxes when using much smaller devices.

The S7000/S9000 are fully compatible with all of the CAD/CAM software you'd expect to run on their workstation cousins. ISV certification and performance drives will be made available for the S-series, just as they are for the W-series. The S7000 and W7000 are identical, apart from the S7000 being passively cooled*. The W9000 and S9000, however, are not. First, here's the W8000/W9000, from our review:

Now here's the S9000's speeds and feeds:

The S9000 really ought to be called the S8600. It's built on the same Tahiti Pro core that AMD uses for the HD 7950/W8000 and runs at the same core clock. Its 6GB frame buffer, 384-bit memory bus, and 264GB/s of memory bandwidth, however, are identical to the W9000. That's significant, given that the S9000's MSRP -- $2499 -- is $1500 less than the W9000's. Our performance tests showed the W8K and W9K performing nearly identically, but if you have a workload that leverages the larger memory pool and higher RAM bandwidth, the S9000 might be a great workstation deal.

AMD's Citrix and VMWare support uses a mode called GPU Passthrough. In both cases, the software allows a virtual machine to directly access a GPU. In this use-case, GPUs and users are mapped in a 1:1 model, with one card dedicated to each client. It's also possible for Xenserver to create virtualized GPUs, with up to four users per card. The implication from AMD's presentation is that Citrix is a bit farther along than VMWare as far as supporting various GPU configurations, and that Remote FX is the most mature solution overall.

As far as we can tell, AMD's Xen/VMware/Microsoft support for GPU virtualization is not identical to Nvidia's VGX. VGX, which the company announced last spring, is a three-part solution consisting of an Nvidia HyperVisor, specific Nvidia VGX boards, and what Team Green calls "User Selectable Machines." Nvidia's VGX boards aren't just repurposed consumer/workstation equipment, either -- they pair four GPUs, 16GB of RAM, and a total of 768 SIMD cores per card.

Nvidia, in short, is throwing more dedicated hardware/software at the problem, while AMD is providing a lower-cost solution that relies more on partner companies to do the heavy lifting. Neither strategy is necessarily better than the other, and we expect the market for this type of workstation deployment to grow modestly over the next few years. In all fairness, we have to note that AMD's presentation on these new cards mentions the "Strong potential for future feature optimizations from AMD" in regards to Microsoft's RemoteFX and says there's the "Potential for VMWare to enable many users to share a single GPU."

That may be more honest language as far as the likelihood of future support, but it doesn't do much to bolster user confidence. If AMD wants to play in the workstation space, it needs to be able to offer potential adopters ironclad guarantees about its own long-term plans. Nobody plans five-year service contracts around a roadmap a company just "probably" plans to execute, no matter what the field.

Microsoft's Remote FX, introduced in Windows Server 2008 and refined for the upcoming Server 2012, allows multiple remote clients full access to a central GPU's capabilities. VMWare and Citrix also offer support for this type of operating mode, but more on that in a moment. The big-picture idea here is that companies can save money and deployment costs by using an array of thin clients. These new cards, dubbed the S7000 and S9000, are meant to facilitate that process. GPU virtualization is a subset of the larger VDI market -- the products AMD and Nvidia have introduced are both aimed at enabling workstation-class users to access the same performance they'd see from high-powered boxes when using much smaller devices.

The S7000/S9000 are fully compatible with all of the CAD/CAM software you'd expect to run on their workstation cousins. ISV certification and performance drives will be made available for the S-series, just as they are for the W-series. The S7000 and W7000 are identical, apart from the S7000 being passively cooled*. The W9000 and S9000, however, are not. First, here's the W8000/W9000, from our review:

Now here's the S9000's speeds and feeds:

The S9000 really ought to be called the S8600. It's built on the same Tahiti Pro core that AMD uses for the HD 7950/W8000 and runs at the same core clock. Its 6GB frame buffer, 384-bit memory bus, and 264GB/s of memory bandwidth, however, are identical to the W9000. That's significant, given that the S9000's MSRP -- $2499 -- is $1500 less than the W9000's. Our performance tests showed the W8K and W9K performing nearly identically, but if you have a workload that leverages the larger memory pool and higher RAM bandwidth, the S9000 might be a great workstation deal.

AMD's Citrix and VMWare support uses a mode called GPU Passthrough. In both cases, the software allows a virtual machine to directly access a GPU. In this use-case, GPUs and users are mapped in a 1:1 model, with one card dedicated to each client. It's also possible for Xenserver to create virtualized GPUs, with up to four users per card. The implication from AMD's presentation is that Citrix is a bit farther along than VMWare as far as supporting various GPU configurations, and that Remote FX is the most mature solution overall.

As far as we can tell, AMD's Xen/VMware/Microsoft support for GPU virtualization is not identical to Nvidia's VGX. VGX, which the company announced last spring, is a three-part solution consisting of an Nvidia HyperVisor, specific Nvidia VGX boards, and what Team Green calls "User Selectable Machines." Nvidia's VGX boards aren't just repurposed consumer/workstation equipment, either -- they pair four GPUs, 16GB of RAM, and a total of 768 SIMD cores per card.

Nvidia, in short, is throwing more dedicated hardware/software at the problem, while AMD is providing a lower-cost solution that relies more on partner companies to do the heavy lifting. Neither strategy is necessarily better than the other, and we expect the market for this type of workstation deployment to grow modestly over the next few years. In all fairness, we have to note that AMD's presentation on these new cards mentions the "Strong potential for future feature optimizations from AMD" in regards to Microsoft's RemoteFX and says there's the "Potential for VMWare to enable many users to share a single GPU."

That may be more honest language as far as the likelihood of future support, but it doesn't do much to bolster user confidence. If AMD wants to play in the workstation space, it needs to be able to offer potential adopters ironclad guarantees about its own long-term plans. Nobody plans five-year service contracts around a roadmap a company just "probably" plans to execute, no matter what the field.