Crushing Competition: Cable Companies Try To Outlaw Google Fiber, AT&T Attacks Net Neutrality

Two events in the telecommunications and cable world this week have highlighted why, exactly, we need net neutrality and stronger protections for consumer rights. First, on the cable side of the business, Time Warner Cable, Cox, Eagle Communications, and Comcast have collectively introduced a bill into the Kansas legislature that prevents any city from rolling out any broadband infrastructure unless said area is completely cut off from the grid.

Critically, the bill also claims that a municipality is "providing a video, telecommunications or broadband service" if it works through intermediaries, partnerships, on contract, or through resale. It would bar the use of eminent domain for the purpose of providing better service to a city's citizens. And not incidentally, it makes Google Fiber effectively illegal. "Unserved areas" are an exception to these policies, except, under the bill's language, an "unserved area" is an area within city boundaries where 90% of people cannot achieve the minimum defined broadband speed according to the FCC. Since satellite Internet technically covers nearly everywhere these days, even if the caps are low and the speeds typically terrible, this means there are precious few "unserved areas" in the contiguous United States.

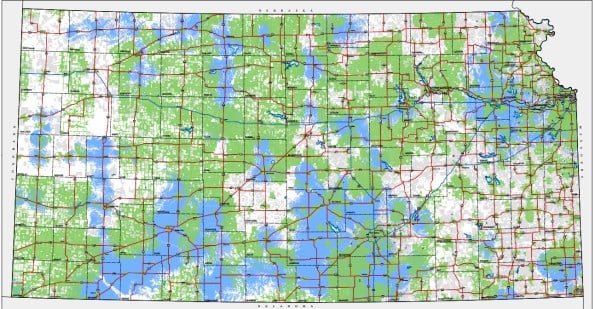

This is an example of how the FTC dropped the ball when it came to setting the definition of broadband. By picking a pitifully low 4Mbps threshold, virtually everything can qualify as broadband, even when actual performance is nothing like what an urban user would actually expect. As a practical example, here's a map of Kansas showing total wired and wireless access above 3Mbps.

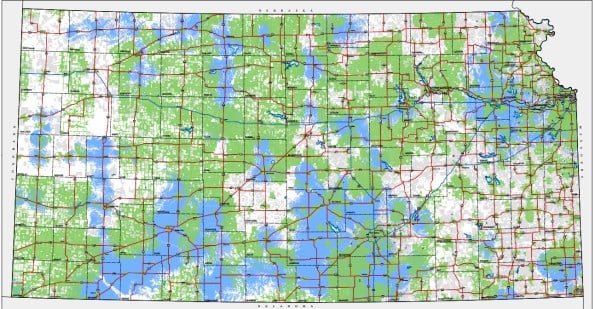

And here's a map of Kansas showing DOCSIS 3.0 rollouts. It's an older map from late 2012, which means the situation may have improved somewhat, but telecoms have dragged out the DOCSIS 3.0 rollout nearly everywhere.

The difference is in how you define "broadband."

The bill would outlaw public/private partnerships, open access approaches, and the partnership that brought Google Fiber to Kansas City. It doesn't have a single sponsor, but was proposed by John Federico, president of the Kansas Cable Telecommunications Association. As Ars Technica writes, the bill has exploded in controversy as a blatant attempt by the cable companies to outlaw competition.

AT&T Attacks Net Neutrality Through Patents

Meanwhile, AT&T has been quietly assembling a patent portfolio for itself that simultaneously attacks net neutrality and consumer rights. The company applied for a patent titled "Prevention Of Bandwidth Abuse Of A Communications System" in October 2012; the patent was actually published in September, 2013. The abstract reads, in part:

Once you have the ability to "know" what all the bits contain, however, you're liable for stopping their transmission. So what AT&T is attempting to patent here is a classic case of eating your cake and having it to. They can penalize you for burning bandwidth in an unapproved activity, or you can just buy Netflix and pay an extra fee so that your data won't count against your broadband cap.

The telecommunications industry is not our friends. These are organizations looking to lock in profits and lock out competition in ways that would've made Ma Bell blush.

Critically, the bill also claims that a municipality is "providing a video, telecommunications or broadband service" if it works through intermediaries, partnerships, on contract, or through resale. It would bar the use of eminent domain for the purpose of providing better service to a city's citizens. And not incidentally, it makes Google Fiber effectively illegal. "Unserved areas" are an exception to these policies, except, under the bill's language, an "unserved area" is an area within city boundaries where 90% of people cannot achieve the minimum defined broadband speed according to the FCC. Since satellite Internet technically covers nearly everywhere these days, even if the caps are low and the speeds typically terrible, this means there are precious few "unserved areas" in the contiguous United States.

This is an example of how the FTC dropped the ball when it came to setting the definition of broadband. By picking a pitifully low 4Mbps threshold, virtually everything can qualify as broadband, even when actual performance is nothing like what an urban user would actually expect. As a practical example, here's a map of Kansas showing total wired and wireless access above 3Mbps.

And here's a map of Kansas showing DOCSIS 3.0 rollouts. It's an older map from late 2012, which means the situation may have improved somewhat, but telecoms have dragged out the DOCSIS 3.0 rollout nearly everywhere.

The difference is in how you define "broadband."

The bill would outlaw public/private partnerships, open access approaches, and the partnership that brought Google Fiber to Kansas City. It doesn't have a single sponsor, but was proposed by John Federico, president of the Kansas Cable Telecommunications Association. As Ars Technica writes, the bill has exploded in controversy as a blatant attempt by the cable companies to outlaw competition.

AT&T Attacks Net Neutrality Through Patents

Meanwhile, AT&T has been quietly assembling a patent portfolio for itself that simultaneously attacks net neutrality and consumer rights. The company applied for a patent titled "Prevention Of Bandwidth Abuse Of A Communications System" in October 2012; the patent was actually published in September, 2013. The abstract reads, in part:

A user of a communications network is prevented from consuming an excessive amount of channel bandwidth by restricting use of the channel in accordance with the type of data being downloaded to the user. The user is provided an initial number of credits. As the user consumes the credits, the data being downloaded is checked to determine if is permissible or non-permissible. Non-permissible data includes file-sharing files and movie downloads if user subscription does not permit such activity. If the data is permissible, the user is provided another allotment of credits equal to the initial allotment. If the data is non-permissible, the user is provided an allotment of credits less than the initial allotment.This is actually a profoundly stupid move on AT&T's part, for multiple reasons. Current American copyright law shields online services and ISPs from the actions of their users unless a content owner can prove that the company knew about the infringement and did nothing to stop it. This is known as the "safe harbor" provision of the DMCA. If you're an AT&T customer and you upload a movie to a video service, AT&T isn't liable for the contents of that video because AT&T had to way of knowing that the video bits infringed on copyright owner rights.

Once you have the ability to "know" what all the bits contain, however, you're liable for stopping their transmission. So what AT&T is attempting to patent here is a classic case of eating your cake and having it to. They can penalize you for burning bandwidth in an unapproved activity, or you can just buy Netflix and pay an extra fee so that your data won't count against your broadband cap.

The telecommunications industry is not our friends. These are organizations looking to lock in profits and lock out competition in ways that would've made Ma Bell blush.