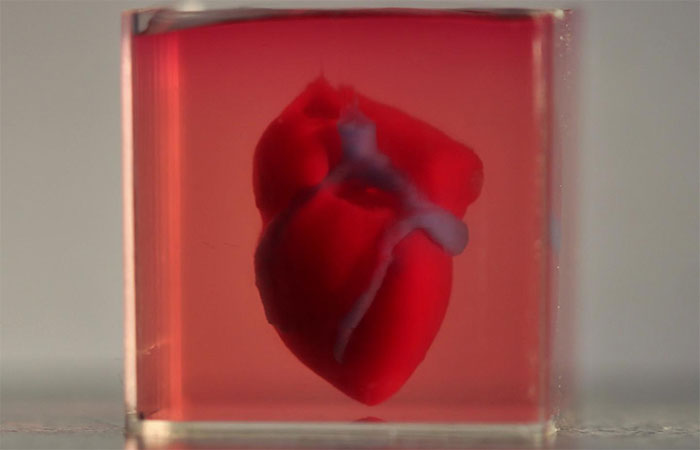

Scientists 3D Print Mini Human Heart Using Patient’s Own Cells

There is hope that one day in the perhaps not-too-distant future, organ donors will not be needed. Not because the human race is going extinct (thought that's certainly a possibility), mind you, but because scientists have achieved a medical breakthrough by producing the world's first 3D printed heart, using a patient's own cells.

One of the reasons why this is such a big deal is because heart disease is the leading cause of death among men and women in the United States. For patients who find themselves with end-stage heart failure, a transplant is the only option. Donors are obviously in short supply, compared to the number of people who could use a heart transplant.

Up until now, scientists in regenerative medicine have not been able to 'print' a heart with blood vessels, only simple tissues.

"This heart is made from human cells and patient-specific biological materials. In our process these materials serve as the bioinks, substances made of sugars and proteins that can be used for 3D printing of complex tissue models," says Professor Tal Dvir of TAU's School of Molecular Cell Biology and Biotechnology and lead researchers on the study. "People have managed to 3D-print the structure of a heart in the past, but not with cells or with blood vessels. Our results demonstrate the potential of our approach for engineering personalized tissue and organ replacement in the future."

The 3D printed heart is replete with cells, blood vessels, ventricles, and chambers. However, it's not suitable for transplanting into a human, at least not yet. It is far too small—about the size of a rabbit's heart, Professor Dvir says. Printing larger human-size hearts requires the same technology, though, so there is hope.

One of the risks with heart transplants, or any kind of organ transplant, is that the host will reject the donated part. That's where using the patient's own cells to 3D print a heart can help, though there are other challenges.

"We need to develop the printed heart further," Professor Dvir says. "The cells need to form a pumping ability; they can currently contract, but we need them to work together. Our hope is that we will succeed and prove our method's efficacy and usefulness."

This won't happen overnight, though it won't several decades, either. At least, the researchers hope not. Professor Dvir reckons that in maybe 10 years, we will see 3D printed hearts routinely transplanted into humans.